The technology that resurrected the Herculaneum library

Thanks to technology, how many mysteries of the past are we able to rediscover? Among these certainly that of the papyri of the ancient library of Herculaneum.

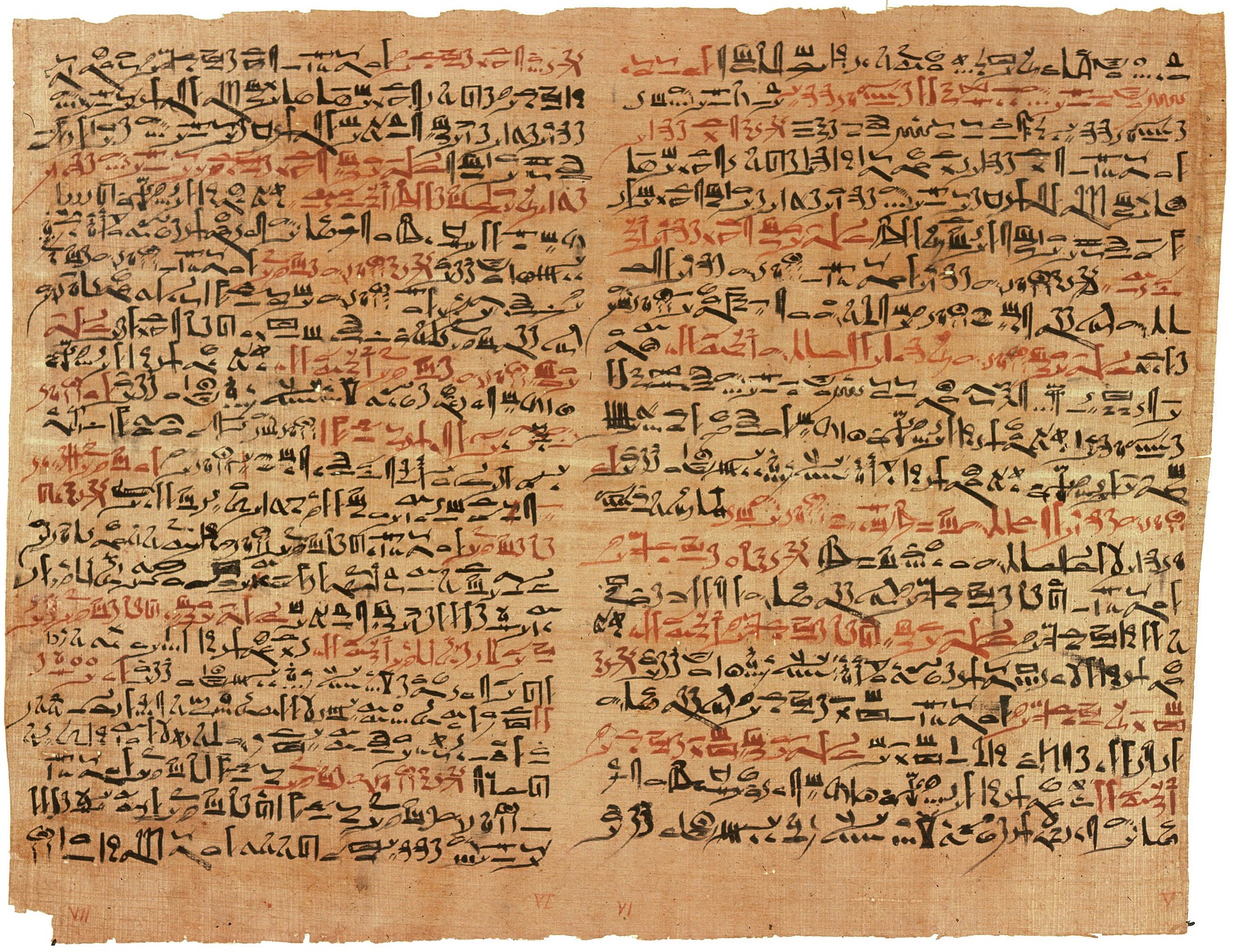

Let’s quickly reconstruct its history. The eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD covers Pompeii and Herculaneum with mud and ash and protects the two cities from history and the changes of time. Also buried is a beautiful villa with an enormous library of papyrus rolls: secrets of Roman and Greek philosophy, science, literature, mathematics and politics, hidden by charred rolls but perfectly preserved, just waiting to be beds.

Almost 1700 years will pass before this library is rediscovered: digging a well, a farmer finds a Roman floor. The excavations will bring to light the statues and frescoes of the villa, as well as many rolls. They are charred and therefore very fragile, but being able to read them would significantly increase the amount of writings and testimonies of antiquity. The first clumsy attempts to unroll the papyri will destroy many; others, subsequently, will be opened by an Italian monk who, with great care, over the years, will take care of verifying their contents. These are philosophical texts written in Greek: more than six hundred remain closed and unreadable and many historians believe that there are many more still underground, not yet discovered.

But let’s go back to the present: it is 2015 when the team of Dr. Brent Seales, thanks to the virtual scrap, manages to read the scroll of En-Gedi, a manuscript in Hebrew which is thought to be the oldest representation of the Bible. A find so compromised that it was in no way possible to unroll. The team of scientists uses X-ray tomography and artificial vision: these techniques make it possible to digitally unroll and read a carbonized scroll, without physically opening it and therefore without further compromising its state of conservation. However, the Herculaneum papyri have a carbon-based ink, not very dense and therefore unsuitable to be read by X-rays.

A few years later, Dr. Seales’ team makes a different attempt. Infrared light detached fragments are readable and are then used as basic data for a machine learning model that can detect ink otherwise invisible to X-rays. By increasing the resolution of X-rays with a particle accelerator, it is possible to scan whole scrolls and several fragments: Machine learning models appear to be able to detect subtle surface patterns in papyrus, which indicate the presence of carbon-based ink. Just at the beginning of this year, the turning point occurs: the machine learning model recognizes the ink from X-ray scans, thus giving the possibility to apply the virtual waste also to the Herculaneum papyri.

The process therefore consists of 3 steps: the scan, which creates a 3D version of the scroll or fragment, using X-ray tomography; segmentation and flattening, which finds the layers of rolled papyrus and unrolls it flat; ink detection, which identifies written regions in the flattened surface thanks to a machine learning model.